There's no question that the Irish have had an outsized influence on the world — and it's not just about great literature and song. Imbued deep in the Gaelic character is a natural generosity, born of lived struggle and inequity across the generations.

When it comes to charitable giving, the Irish are among the most generous in the world. The World Giving Index puts Ireland at number 9 in its most recent 10-year aggregated global ranking of the most altruistic countries (the US is at number 1.)

While the island itself has a population of just under 6 million, there are as many as 800,000 Irish-born people living abroad, an estimated 3 million Irish passport holders outside of Ireland, and well over 50 million people around the world who claim Irish ancestry.

Irish Americans in particular have proven to be extremely generous — donating hundreds of millions of dollars over the past two decades to support the work of organizations like Concern. We’ve been reflecting on why that might be. Here are our top 4 reasons:

1. Hunger

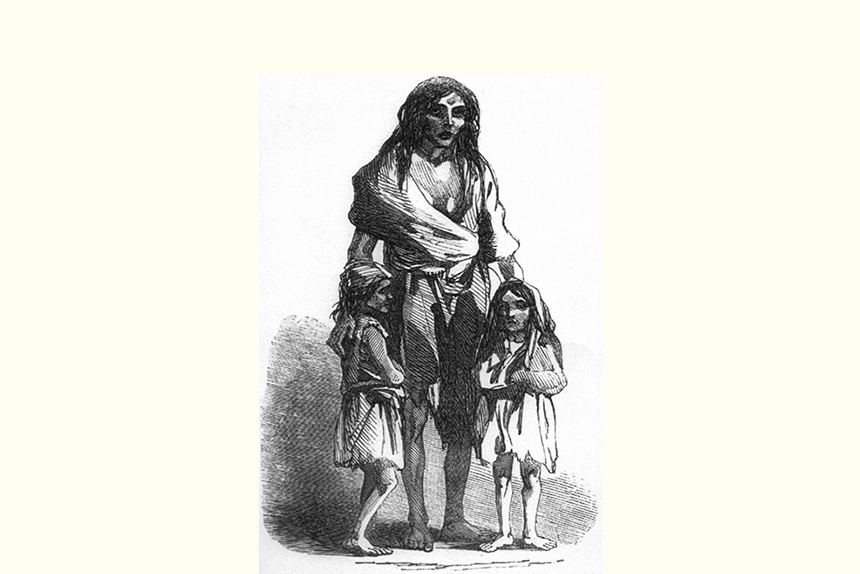

As many as 1 million Irish people died of hunger during the Great Famine, the catastrophic failure of successive potato harvests in the 1840s. Another million emigrated in the years following. Those numbers are staggering, given that they represent roughly 20-25% of the Irish population at the time, and this has undoubtedly left a lasting imprint on the collective Irish and Irish-American consciousness.

Towns and villages were ravaged and a generation pulled apart by “the famine.” Invariably it was the poorest who suffered the most, and they generally lived in the remotest rural parts of the country.

More than a century later, we would once again witness the devastating effects of famine — this time via TV images beamed into Irish homes from remote, rural areas of the developing world: places like Biafra, Ethiopia, and Somalia. The response was incredible, both from Ireland and its scattered diaspora, and that spirit of generosity continues to this day.

"We all live in each other’s shadows.”

Former Irish President, Mary McAleese, quoted on the walls of the Irish Hunger Memorial in New York City, sums it up: “In commemorating victims of the Irish Famine, we must renew our pledge to feed the hungry and to end the scourge of famine and poverty worldwide. We all live in each other’s shadows.”

2. Migration and discrimination

The million emigrants fleeing famine were just the beginning. Over the past century there have been constant waves of migration from Ireland, mostly to the UK, USA, and Australia, and mostly for economic reasons.

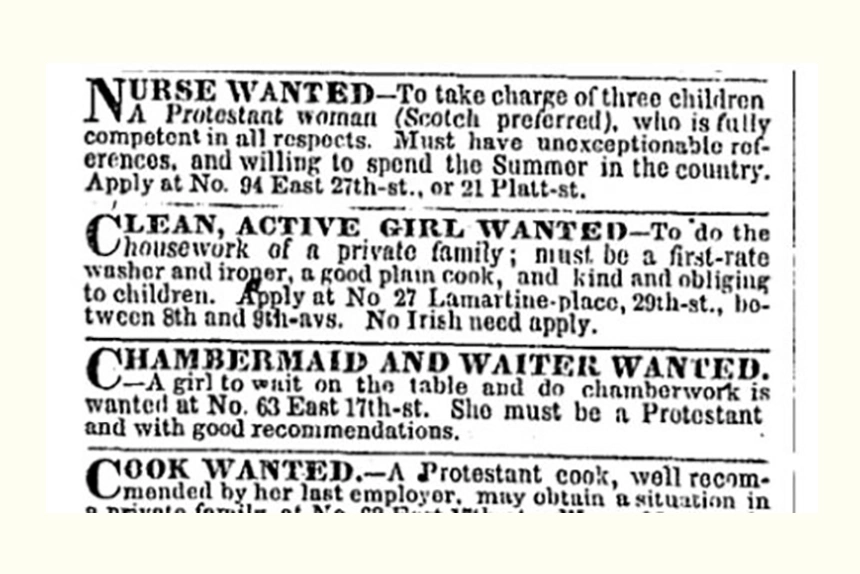

Many Irish who landed on foreign shores in the 19th century were met with hostility and discrimination. Often they were under-educated, lacking in requisite skills, and hampered by a poor command of the English language. Religious (anti-Catholic) discrimination was a major factor too. Signs reading “No Irish Need Apply” were not unusual on the streets of London or Boston a century ago.

Speaking at a Concern fundraising event in New York in 2018, Irish musician and longtime anti-poverty activist, Bono, said "We were the stranger, we were the invading hordes, we were the cockroaches, and we haven’t forgotten."

Until the 1980s, those who left had little prospect of ever returning home, but their connection with the homeland remained strong, and remittances from abroad became a valuable source of income for struggling families in Ireland.

Fast-forward to the 21st century and it’s easy to see how Irish people can empathize with those who face many of the same challenges. Economic migration, discrimination, religious bias, and ethnic hostility have not gone away — only the faces have changed.

And money earned abroad is still a lifeline to communities across the developing world. In 2022 an estimated US$3.1 billion was sent to Haiti by its diaspora living and working abroad, 80% of it from the United States.

3. Poverty (a very recent memory)

It’s really not that long ago that Ireland would have been considered a developing country. Like many of the nations today in receipt of foreign aid, the Irish emerged from colonization in an impoverished condition.

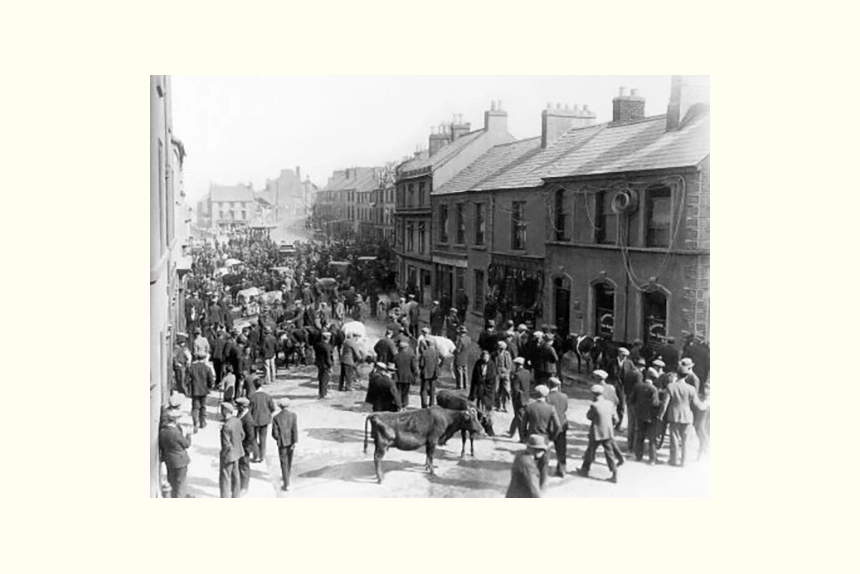

Infrastructure outside of the cities was limited. There are people alive today who remember collecting water every day from communal “parish” pumps — very similar to what you’ll see in images from countries where Concern works now. Much of rural Ireland did not get electricity until well into the 1960s and some outlying areas remained off the grid into the 1970s.

Diseases like tuberculosis killed upwards of 10,000 Irish people a year until it was finally eradicated in the 1950s, and childhood mortality remained considerably higher than neighboring countries until the late 1960s. If you’re Irish and over 70 there’s an above-average chance you lost a sibling or a cousin in childbirth or infancy.

All of this underscores the point that, as a nation, the Irish are closer than most in the “developed” world to understanding through recent experience the problems facing people in rural areas of countries like Malawi, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

Over the last half-century, the Irish influence in helping these communities to overcome some of their biggest development challenges — in fields as diverse as agriculture, education, health, livelihoods, sanitation, and water — has been significant.

We're keenly aware that the “easy fix” is an exercise in futility, and that achieving meaningful and lasting change is complicated... and difficult. But that's okay, and everything is easier when you work together.

Help us in the fight against extreme poverty

4. Attitude

Due in part to a combination of the above factors, it's fair to say that the Irish have a reputation as a can-do, scrappy, no-nonsense bunch. Despite all of the obstacles and challenges, they have gone on to have a significant influence on the world at large. And that includes the business of helping others.

Irish missionaries tasked with spreading the Catholic faith in Africa during the mid 20th century soon realized there were more pressing matters to be addressed. Priests and nuns rolled up their sleeves, built schools and clinics, and got down to the business of helping people improve their everyday lives.

Soon these missionaries would be followed by agencies like Concern, who brought professionally qualified volunteers, nurses, engineers, agriculturalists, and teachers ready and willing to use their time and knowledge to good effect. These agencies would go on to become the organized, systematic, programmatic NGOs that have helped transform the lives of hundreds of millions of people in the intervening decades.

We rest our case

These are just 4 of the many reasons we believe that being Irish means being a giver.

Despite — or perhaps because of — our story of challenge and survival, we retain an indefinable and distinctly Irish sense of social justice, hard work, invention, innovation, generosity… and good humor.